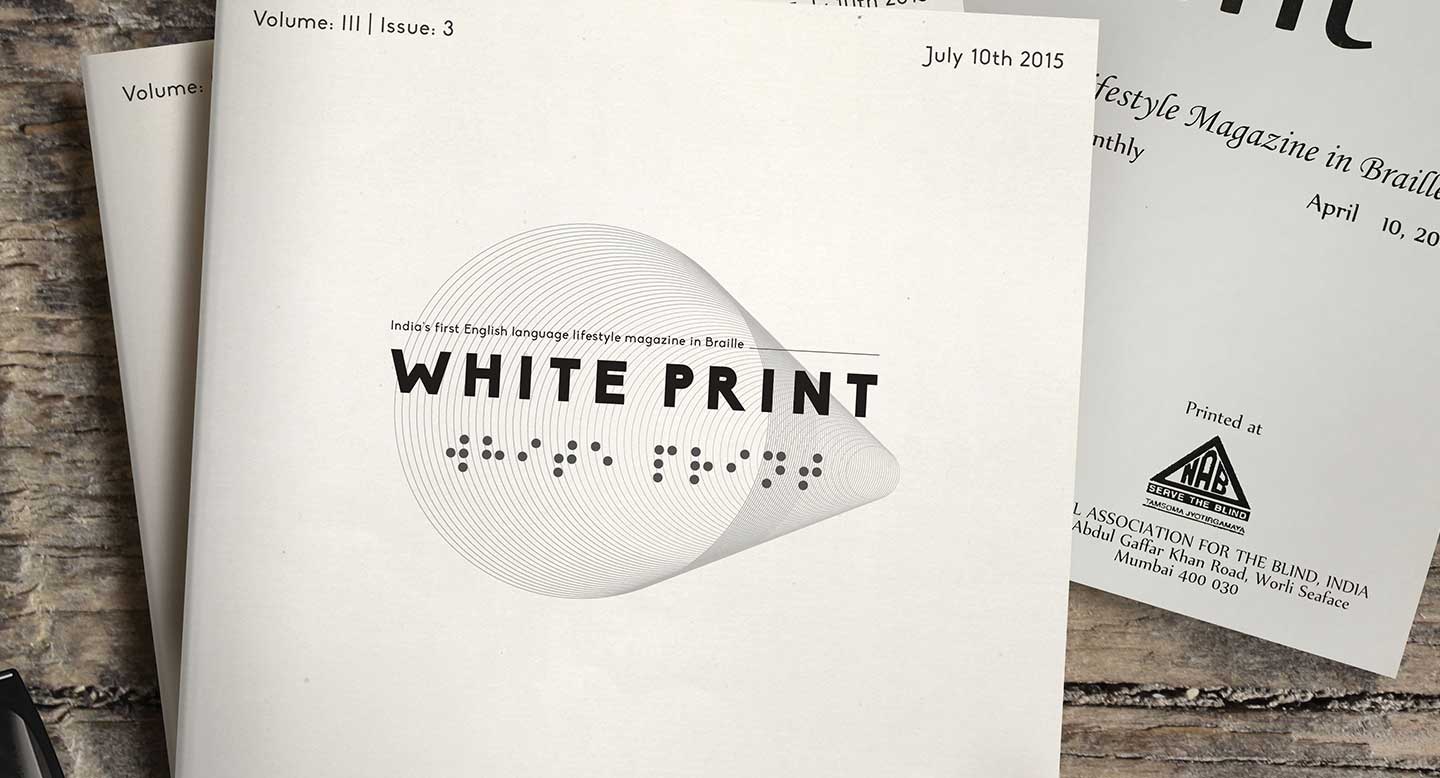

Banking on advertising revenues, young entrepreneur Upasana Makati is publishing a multi-faceted literature magazine for the visually impaired in India, while creating awareness about the need to teach Braille literature for them through her maiden initiative, B for Braille

When Upasana Makati was figuring out how to improve the quality of content in her Braille magazine, White Print, she remembered a conversation she once had with one of her readers, a visually impaired girl. The reader said, every time I step out of the house, I have to apply my favourite brand of lipstick endorsed by actress Katrina Kaif. “I naively asked her why she likes Katrina and she said, because her voice is beautiful,” recalls Makati. It was feedback like this that led Makati to learn several lessons about developing literature in Braille for the visually impaired. “For one, they also want to know more about and use all the products and services we do and they love reading about anything, from fashion to entertainment to politics and short stories,” she cites.

Solely dependent on advertising revenues, White Print now banks on this one woman army who is supported by a few freelance writers. “I write two to three columns every edition, and through editorial partnerships with publications such as Caravan, I receive one article every month,” she notes. In fact, her magazine also boasts of political columns from renowned journalists such as Barkha Dutt, and enjoys a readership of 400 people across schools, colleges, healthcare institutions and individual subscriptions. “The journey hasn’t been easy. But I look at the positives and feel, I can now take up new challenges and face them head on,” she says.

Tracing Back the Journey

A graduate in Mass Communications from the University of Ottawa, Canada, Makati was content with a job at a Public Relations agency. Yet, every night when she lay down on her bed, she had a nagging feeling that she wasn’t using her potential to its fullest. “There were several occasions when I would discuss with my friends about doing something more but we never found an answer to it,” she recalls. And then, one night as she sat to review her day, a thought struck her out of the blue, what do the visually impaired read? What kind of literature is being developed for them? This question led her from Google to the gates of the National Association for Blind, where she found that if anything, there were only monthly or quarterly newsletters created for them. “I was shocked. Then I asked them, what if I create a magazine for them?”

The Legal Process

It took Makati eight months and two failed attempts to firm up on a title for the magazine. During this process, she banked on the money she received from freelance jobs to keep the dice rolling. “I remember, after the first failed attempt, I approached an advocate who said it would cost Rs. 40,000 to get the magazine registered. I said I can’t afford it and in the third attempt, I succeeded by just spending Rs. 10 on it,” she chuckles.

She was clear that she didn’t want to establish the business as an NGO but as a for-profit business because she wanted to bust the ideology that the visually impaired need to be sympathised with. Hence, she decided to bank on revenues from advertisement to keep the publication alive. “Initially, we made many cold calls and sent several emails to companies but there wasn’t much recall. Then, we decided to directly get in touch with the marketing heads and founders. The first company which signed the deal with us was Raymond. They gave a five-page advertorial about their Spring-Summer collection,” shares an enthusiastic Makati. Ever since, the magazine has invited advertisements from the big guys like Coca Cola, Vodafone and Aircel, which set the pace for Makati to approach other big ticket clients to advertise in her magazine.

“There was a time when we didn’t have advertisers for six months. Even then, what kept us going was the encouraging feedback we received from our readers.”

While this helped sustain her venture, another key advantage she had was that the Government does not levy postal charges for literature in Braille. Hence, she didn’t have to incur distribution costs. From the first release in May 2013, the magazine has continuously taken reader feedback and expanded content in its magazine to include a variety of features on travel, lifestyle, music, politics, entertainment and more. “While initially, we were targeting readers between the 18 – 35 years age group, today our youngest reader is 11 and the oldest is 80,” she shares.

Stepping Into the Future

Since there is very limited Braille literature available in the market, a lot of visually impaired people began shifting to audio. Additionally, unless they learnt how to read Braille, they wouldn’t be able to access books or magazines. Keeping this in mind, Makati and a team of directors and production managers developed a five-minute short film titled ‘B for Braille’. “The ratio of visually impaired and literate visually impaired is heavily skewed in India. There is an urgent need to educate and empower them,” she opines. In fact, everywhere she goes, she makes it a point to play the video because it creates a deep impact in the minds of the viewers.

In the coming years, Makati has a clear goal in mind; to increase subscriptions for the magazine and to eventually, write books about developing content for the visually impaired. “There was a time when we didn’t have advertisers for six months. Even then, what kept us going was the encouraging feedback we received from our readers. This showed that what we were doing was worth the while,” she states, on a parting note.