Anusha Rizvi’s charming debut Peepli[Live] does with great restraint and subtlety what Madhur Bhandarkar’s Page 3 tried to do with stereotypes and clichés. In choosing a real issue as its backdrop, as opposed to the reportage of the lives of the rich and famous, it also definitely asks to be taken more seriously. However, as a favourite critic of mine sharply noted, other than the perfunctory poignant factoid at the end of the film, Peepli[Live] stays faithful to its title, keeping its focus firmly on the media mayhem and relegating the issue of farmer suicides to the background. To a constantly wandering mind like mine, the things out of focus hold as much value and interest as those in focus, and off I went on my little thought trip. There has been a lot said and written about dying farmers and much discussion has sprung forth on what the Government is doing wrong and what it should do right. Shockingly, I do not have an opinion on this and I am not going to attempt to offer my version of the armchair expert’s magical fix for yet another intractable problem. All I plan to do, as regular readers should know well by now, is ask questions, the most important ones among them being- Why is agriculture not looked at as a viable career option for the educated in India? Could it be possible that the lack of infusion of educated people into agriculture in India has kept it stagnant without significant progress for decades?

Questions and no answers

In India, the commonest deterrent to making educational choices other than medicine and engineering is financial uncertainty. But, that surely cannot be the case in a field, pun unintended, which caters to a basic human necessity. Let us face it- struggling farmers are not a universal phenomenon. Farmers in developed countries who have been exposed to the benefits of technology, have readily adopted it as a means to improve productivity drastically, and this has contributed to some sort of an industrialisation of agriculture. With education comes modern scientific farming methods and practices and ways to overcome the vagaries and uncertainties of nature- the biggest threat to profitability. Why then is this not an attractive means of livelihood? Is it because it is perceived as an ‘uncool’ vocation? A vocation that does not challenge the intellect? As to the former, I think one of my top ten cool jobs would be growing grapes in my own vineyard or barley in a little farm on the hills. One can clearly see what drives my spirit, pun intended, but, on a serious note, conventional career paths do not always end in rocket scientist jobs. Is it because it requires a regressive move from cities to villages away from the sphere of comfort one has grown up in? But, is not any new job going to involve that breaking away from the familiar?

Do parents guide or do they goad?

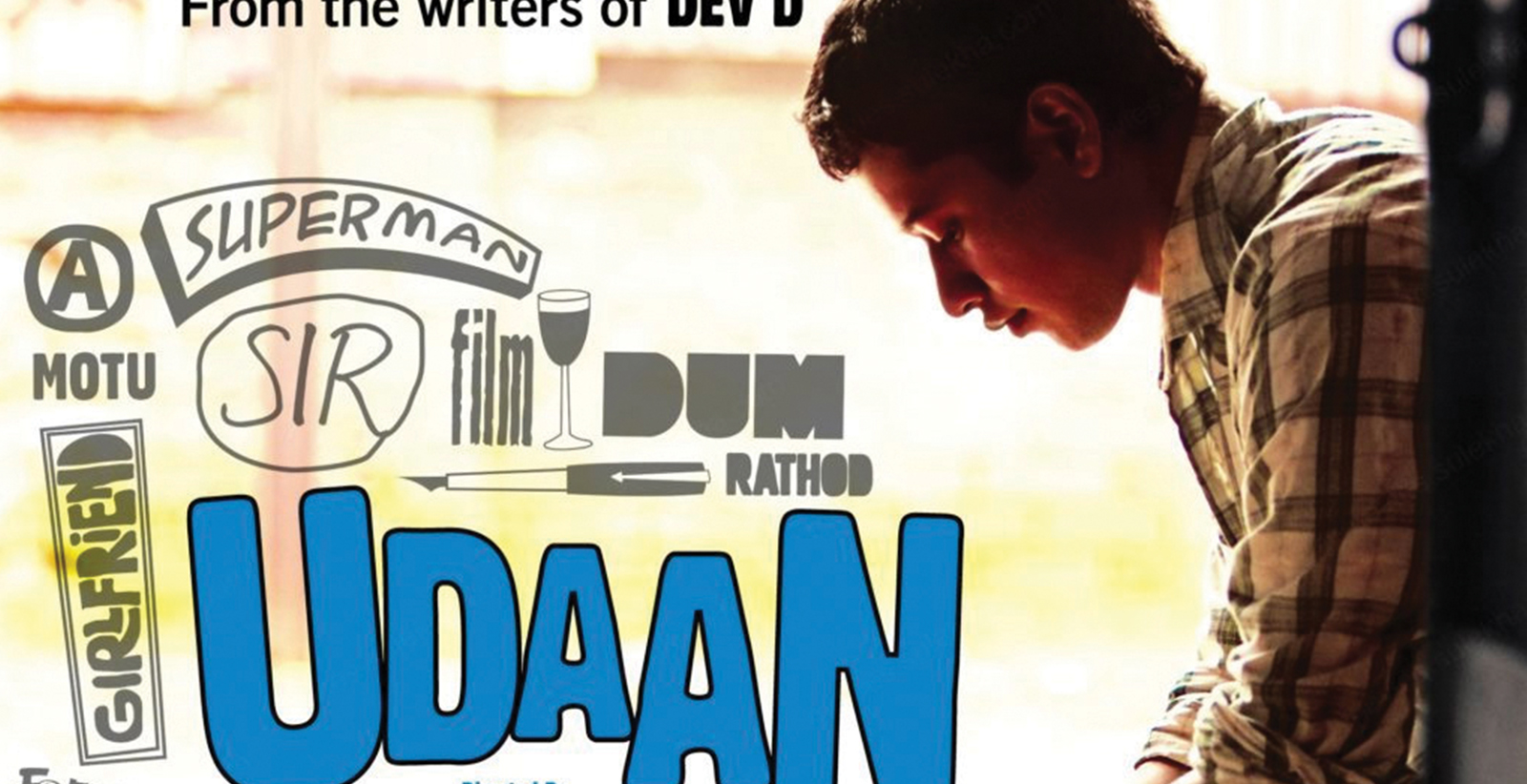

Or above all is it really because of that not spoken about but undeniable, elephant in the room that has an overbearing effect on our choices-parental influence? Granted we are at a generational cusp where parents are beginning to realise that letting their children make their own choices and decisions allows them a better quality of life. Still, a sizable proportion of parents impose their view of what is right for their children, paying little heed to their interests, likes and dislikes. As the movie Udaan beautifully explores, having to bear the burden of your parent’s choices with respect to your education can be a stifling, constricting experience. A strict authoritarian father, with some complex character traits not commonly seen in Indian cinema, however conforms to the reliable stereotype of an Indian parent who wants his son to do engineering when he wants to become a writer. The real issue is the fact that going against convention, even if that is genuinely what the child wants to do, is perceived merely as an act of rebellion.

Parents continue to gauge careers as purely economic choices, when in reality they are much more than that. And when children thrust unwillingly into conventional careers end up being successful in them, parents like to reiterate that it was all for the good. It is like clipping the wings of an eagle and being happy that it can still outrun all the chicken, a pity considering it was meant to soar the skies. Hopefully it will all change with a generation that cares little for custom and convention. Who knows, if I play my cards right, thirty years from now, I might be on a wine tasting tour of my daughter’s vineyard. But then again, that depends entirely on how she chooses to play her hand, does it not?