When I made the decision to move back to India after living abroad for five years, there was very little thought involved. Many people asked if I was completely aware of, and prepared for what the move really entailed. Initially, I found this absurd, for five years is not too long a time to grow roots in a place, at least the kind which would be difficult uprooting, but then maybe it is more than enough time to get spoilt by all the good that a place can offer. Yet, there have been no surprises nor major readjustments needed in the one year I have been back, except maybe for that one little incident a month ago. I was travelling in an auto-rickshaw when we were rather rudely stopped by a bunch of men waving trade union flags, with one of them hopping on to the moving vehicle. They then proceeded to berate the driver for plying on the day of a strike, deflated the front tyre of his vehicle and one of the men, who had been a mute spectator all along, made a disrespectful wave of his hand motioning me to get out and be on my way. Now having been reared on good old Indian cinema, my blood boiled, my muscles tensed, my teeth gnashed, my fists clenched and then I silently walked the remaining half a kilometre to my destination. When I think about this event, I sometimes feel like I am overreacting to something trivial, but when the reason for the strike was to protest a government decision to allot more auto licenses and the fact that the union guys could, unquestioned and unchecked, bully a driver who did not really care about the increased competition, and force him to join them against his will, I am convinced I am justified in seeing it as a big deal. It is not hard to imagine the same scenario with a shopkeeper union forcing one of their own to shut down because a retail giant was allowed to open a store. Notwithstanding that this kind of a protest is aimed at depriving a consumer of better choices and the new entrants a means of livelihood, the more disconcerting aspect is that an individual is denied the freedom to run his business and life the way he wants it.

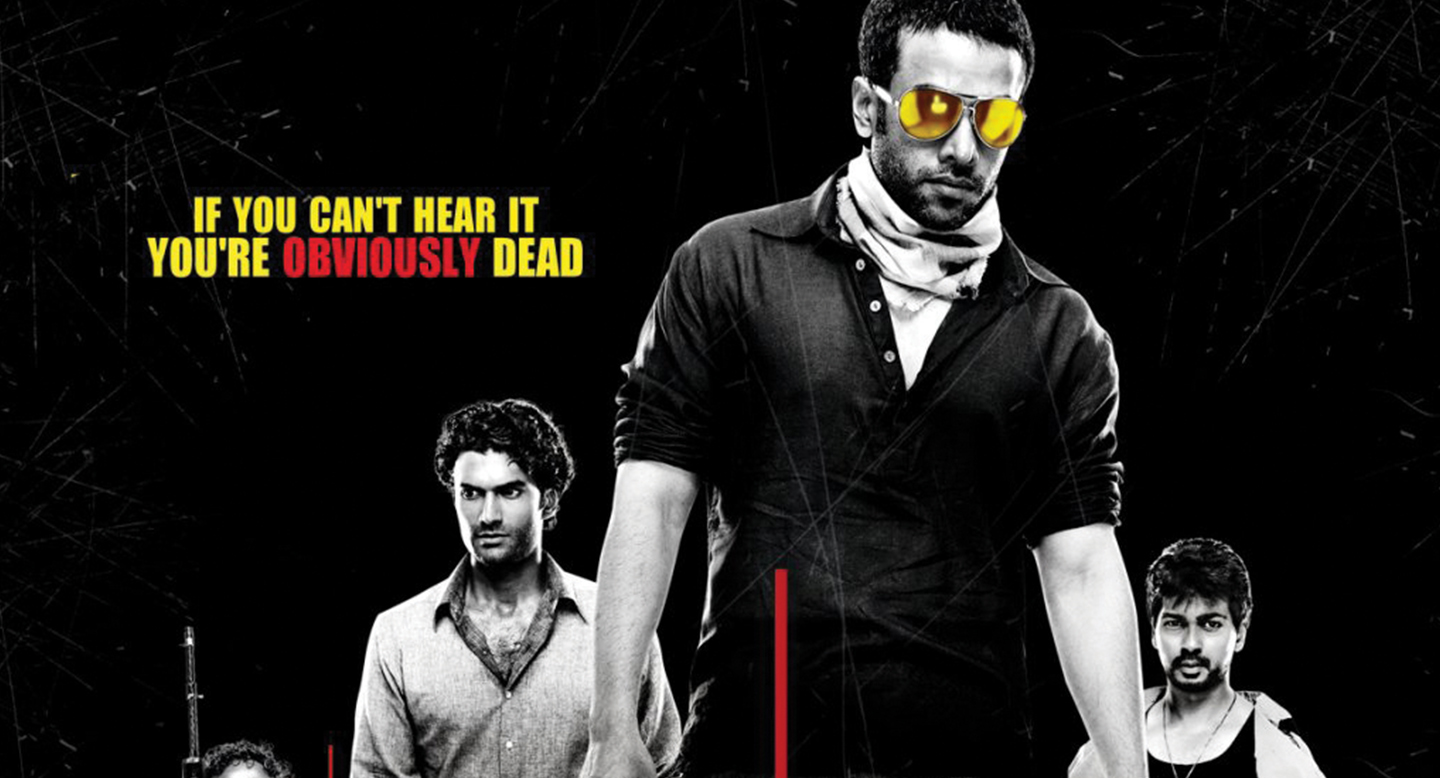

Shor in the City, a rather impressive effort by the director duo of Krishna DK and Raj Nidimoru, explores the travails of a man who returns to India and tries setting up a small business.

Shor in the City, a rather impressive effort by the director duo of Krishna DK and Raj Nidimoru, explores the travails of a man who returns to India and tries setting up a small business. Only, this time he does not encounter the usual government and bureaucratic hindrances, or any form of union opposition, but instead has to deal with a bunch of slimy extortionists. The casual way they approach him, offering his business ‘protection’, presumably from others like them, and the way they start stalking him, encroaching in his private life and gradually revealing their darker side with menace, and ultimately forcing him to yield to them is staged wonderfully. Even when he tries to approach the law, he is only met with a more polished form of extortion, with similar offers of ‘protection’. When he realises that paying them once merely opened the floodgates and pulled him deeper into the mire, he decides to take things into his own hands. While one might think this is a rather cinematic depiction of the challenges faced while starting or running businesses in India, the fact that this is based on a true story makes it all the more credible. It is not just frustrating that there are people like these who can make a quick buck out of one’s hard work, but that they can do so with no easy means of legal persecution and no way out for the affected is rather worrisome.

The other parallel thread in the movie is about a trio who make a living out of book piracy, running a small publishing unit which churns out duplicate copies of bestsellers. The most fascinating aspect is how I did not see them in the same light as the extortionists – as lowly criminals, when in fact their crime is not very different. While an extortionist is more blatant in his act of taking away one’s earnings, these guys do the same thing in a more veiled, nondescript way. This dichotomy, in my perspective, is maybe because of the way they were portrayed in the movie, as more fleshed out characters with details of their personal lives shown, or maybe because the detrimental effects of piracy are not as obvious to see as that of other crimes. One just assumes that big publishing houses and music labels, as well as authors and musicians are well insulated from the losses due to piracy, but it is easy to lose sight of the small bookshop or music store that is affected and loses a significant chunk of its business.

In the current climate of a strong anti-corruption movement, deeming it the single biggest obstacle to India’s progress, one cannot help but wonder if that is merely one step in peeling the onion.